The buyback vs investment debate is back this week, spurred by a column by Bloomberg columnist Barry Ritholtz, who cites General Electric, IBM, and Exxon Mobil as examples of misguided policy, given that their current share prices are well below the levels at which large repurchases were made by each.

“There must have been a better use of those funds than stock buybacks,” Ritholtz writes. “IBM created Watson, more or less as a publicity stunt. While the company was not investing in turning that into a product, Amazon rolled out its Echo, powered by Alexa. GE missed a number of opportunities over this period, as did Exxon.”

Perhaps so, but by focusing on just a few companies, Mr. Ritholtz misses the bigger picture. The chief job of executives is to increase shareholder value, and the historical data strongly suggest that, in aggregate, share repurchases have proven themselves to be effective in adding value for shareholders.

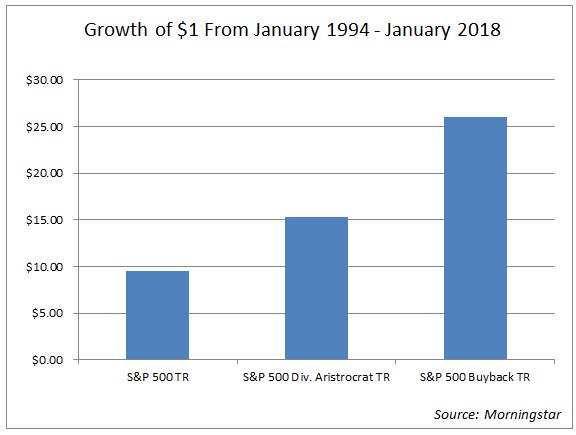

Consider that over the last two decades, stock buybacks (as measured by S&P’s buyback index) have turned a $1 investment into more than $25, outpacing both S&P’s Dividend Aristocrat index and the S&P 500 itself by considerable margins:

Now, buybacks are famously criticized as being ‘short-term oriented,’ and, in the above example, it is fair to say that while I have demonstrated the efficacy of buybacks at least relative to the alternatives of dividend payers and the broad market, I have not compared buybacks to what you might call a ‘long-term’ portfolio, such as one focused on capex-heavy companies like Amazon.

Regrettably, to my knowledge there is no such alternative index that pools companies together based on their capex spending or research & development, but we can take a shot at reproducing a proxy portfolio that might give us some insight into this debate. Thankfully, in 2012, the Progressive Policy Institute put together just such a ‘portfolio’ in a report titled, “U.S. Investment Heroes of 2013: The Companies Betting on America’s Future.” The portfolio consists of the twenty-five largest corporate investors based on their estimated 2012 capital expenditures (via PPI):

To see if these shareholders of these companies have been rewarded for their ‘long-term focus’ I ran three simulations. The first simply shows the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of each company from 2013 through February of this year. The second simply shows the hypothetical CAGR of a portfolio of the above companies had equal amounts been invested in each at the start of 2013 and held through February. The results of this portfolio are quantified in the below graphic as the “Capex Portfolio.” Finally, because the S&P 500 Buyback Index is equally-weighted and rebalanced quarterly, I ran the numbers for the “Capex Portfolio” with these added dynamics. The results are as follows: [Note that due to a 2016 merger, Time Warner Cable is excluded from the simulations.]

It is worth noting that of the twenty-four companies, only seven outperformed the S&P 500 over this period (those shaded in blue), while each of the simulated “capex portfolios” underperformed the index. The S&P 500 Buyback Index surpassed both “capex portfolios,” the S&P 500, and all but five of the companies studied. To be fair, however, there has likely been a good deal more turnover in the buyback index whereas for the capex portfolio I have arbitrarily cited the projected top capex spenders from 2012. Other big capex spenders likely would have replaced the original twenty-four companies at some point over the last few years, and perhaps would have gone on to perform better.

That being said, the point remains that while buybacks are not universally a panacea for shareholders, neither is “investment” in the future. For one thing, as I have written before, capital expenditures are largely cyclical and concentrated in a few capital-intensive industries such as utilities and energy. Most importantly, however, as economist John Cochrane frequently points out, not every investment is worthwhile, and part of the allure of buybacks is the signal to shareholders that management will not fritter away precious capital on dubious projects. Hopefully this analysis has helped investors realize that the buybacks vs investment narrative is really predicated on a false dichotomy.