Except perhaps for stock buybacks, there is no area of investing that suffers from as much misinformation and misunderstanding as dividends. Whether fed by institutional advertisements using them as a marketing ploy, or perhaps because investors perceive them as tangible wealth in an otherwise uncertain investment world, investors have become infatuated with dividends. Unfortunately, very few investors seem to understand dividends, both in terms of what they represent to stock owners, and in terms of their investment utility to a portfolio.

Now, to be sure, dividends are crucial in the aggregate. As Rob Arnott wrote several years ago, dividends have been the source of the lion’s share of historical equity returns, particularly when reinvested. Furthermore, this is not unique to the U.S. market; in fact, dividend payers have outperformed in just about every global equity market. So, to quote Rob Arnott, “Dividends, unequivocally, matter.”

That being said, dividends in and of themselves do not make investors wealthier. This is a mathematical fact as the cash distributed to investors via dividend reduces the per share stock price by an equivalent amount. In a sense, all that has been made is an exchange from ‘perceived value’ to ‘tangible value,’ by which I mean an exchange from a perception of a company’s future earning potential in the form of its present stock price to tangible value in the form of cash on hand for the investor. The key point, of course, is that now the investor rather than the company has discretion over the reinvestment of this capital.

However, if dividends themselves do not create wealth, what explains the historical outperformance of dividend-paying stocks over many competing alternatives?

Not surprisingly, the answer is complex, and involves many variables. For one, as I discussed a couple weeks ago, companies that return cash to shareholders, – whether in the form of dividends or buybacks, – typically outperform those that reinvest the majority of their earnings. This may be because companies generally do not have a stellar record reinvesting shareholder capital, as Corey Hoffstein mentions here, and Jack Vogel explains here. The argument in this case is that investors applaud humility on the part of corporate boards who acknowledge the limits of their investment abilities and instead return precious capital to shareholders to deploy at their discretion.

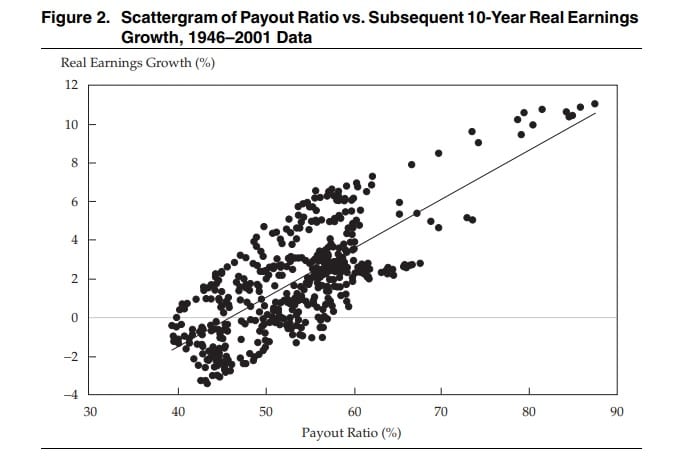

A second explanation is provided by Cliff Asness and Rob Arnott, who demonstrated that higher payouts on the part of corporations have typically been followed by strong real earnings growth:

This surprising relationship between present payouts to investors and strong future earnings growth lends support to the argument that dividends are an indication of a quality company with bright future prospects, not least because it is managed by shareholder-friendly executives who are OK with paying investors today because they know the future for their company is bright.

Finally, and perhaps most practically, as this very helpful Vanguard study explains, dividend stock performance can also be explained by other, perhaps more familiar, factors such as low-volatility and value in the case of high-yield dividend stocks, and low-volatility and quality factors in the case of dividend growth stocks:

Yet despite their brilliant track record, dividends are not without peril for investors. Meb Faber has written several articles on the dangers of infatuation with dividends, focusing particularly on the drag dividends cause on after-tax returns, as well as the poor value signal dividend yield provides relative to other value metrics. In addition, dividends tend to tie the hands of corporate boards, making them reluctant to cut them in times of financial duress. These limitations to dividends explain in large part the shift away from dividends to buybacks, which are more tax-efficient than dividends, and which offer corporate boards much more flexibility in terms of their execution, thus providing investors with a much stronger value signal than dividends provide.

Dividend strategies can and probably should play an important part in any diversified portfolio. However, investors on the hunt for quality issues should be aware of less obvious but often more appealing buyback strategies, and should strive to garner the fullest benefit of dividend strategies by owning them in tax-favored accounts.

Other useful links on this topic:

S&P Indexology: Do Dividends Really Pay?

CFA Institute: What Difference Do Dividends Make?

Tweedy Brown: The High Dividend Yield Advantage