Every investor is aware of Warren Buffett’s famous dictum that, “Price is what you pay; value is what you get.” That of course applies to the valuation an investor is willing to pay for a given company’s stock, and the subsequent returns he receives for doing so. In today’s environment, in which commentary focuses on the lofty multiples that characterize much of the U.S. stock market, particularly on some very popular names like Facebook, Amazon, and Netflix, I thought it would be interesting to revisit the “Nifty Fifty” era of the early 1970s, when the Amazons and Facebooks of the day were what became today’s boring blue chips: McDonald’s, Merck, Procter & Gamble, and so forth.

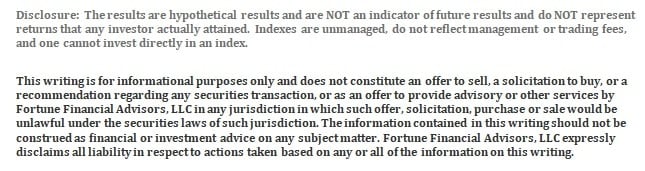

At the peak of the Nifty Fifty ‘bubble,’ many of these stocks traded at extreme premiums to the market, with shares of McDonald’s changing hands at a multiple of eighty-five times earnings, and Coca Cola trading at close to fifty times (data via Brooklyn Investor)*:

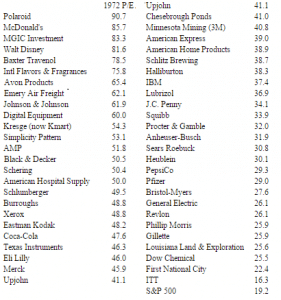

Given these extreme valuations, I wanted to see how investors in those companies fared had they been willing to pay up to own these names. To test this, I decided to pick seven names I considered to be more expensive than others, and seven names I considered to be cheaper. Given that many of the Nifty Fifty names no longer exist due to merger and, in some cases, bankruptcy, I chose for each group names that, as much as possible, exist today more or less as they did then. Additionally, I wanted to control for sector and industry differences as much I could, so both pools ended up heavy in terms of consumer staple and healthcare stocks. Finally, I ran the numbers starting on June 1st, 1972 (the earliest date available to me), and calculated the annualized total return for each stock over the subsequent ten-, twenty-, thirty-, and forty-year periods. Here are the results:

What immediately stands out to me is that, over the initial ten-year period from peak valuation, the cheaper group generally outperformed the more expensive group. It is important to remember that during this period from June of 1972 to June of 1982 there was a huge market crash and lengthy bear market spanning much of 1973-1974. Just about all of these names were crushed during this downturn, so valuation did not really matter during the crash. However, it would appear that the companies with less demanding valuations emerged from the crash in better shape than those with more extreme valuations.

Of the two groups, the two names that jump out to me are Pepsico and Coca Cola. They both are dominant players in the soft drink industry, with global reach. Their business models are not all that different from each other. Yet, at its peak, Coca Cola traded at a 60% premium to Pepsico. At the risk of oversimplifying things, I would suggest that this huge premium played a large part in Coca Cola underperforming Pepsico by almost 1,000 basis points over the subsequent ten years.

On the other hand, over the much longer periods twenty and thirty years, both Coca Cola and Pepsico generated similarly strong results, which suggests that starting valuation matters much less over much longer time frames. This was generally the case for almost all the stocks observed.

The lesson from this exercise, I believe, is that investors should always be conscious of starting valuation when placing their bets. With few exceptions, eventually valuations that are simply too high will drift back down to more reasonable levels, often at the expense of poor intermediate-term performance. This appears to be true no matter how revolutionary the new business appears to be, and no matter how much potential you believe it has. Of course, if your conviction is such that you plan on holding your shares for multiple decades, valuation may indeed matter less to long-term returns, but that is assuming you follow through on your commitment. Over several years of sub par performance, that is much easier said than done.

*Note, Brooklyn Investor does not specify in his post, but the P/E multiple shown is assumed to be based on trailing twelve-months’ earnings.

For further reading, see Professor Jeremy Siegel’s Valuing Growth Stocks: Revisiting the Nifty Fifty, via AAII